Hi everyone, this is an essay that I wrote for our cookbook, The Woks of Life: Recipes to Know and Love from a Chinese American Family, now available wherever books are sold. (If you haven’t already, grab a copy! It has 100 recipes, including 80 that aren’t on the blog, as well as lots of family photos and stories we haven’t shared here!)

Due to space constraints (ahem, we actually wrote about 80,000 words too many in our first draft), we had to cut this essay out of the book.

However, I’ve been wanting to share it with you all for a long time, because I think it lays out the origins of the blog, as well as our family’s evolving philosophy on recipe development. I hope you can relate to it, connect with it, or just get some entertainment out of it. Enjoy!

– Sarah

“How do you know how much to pour in?” I asked my mom, as she streamed soy sauce straight from the bottle into a bowl of dumpling filling.

“It smells salty enough” she said, putting her nose close to the bowl and taking a big whiff. “Needs more wine.”

“How does something smell salty?” I ask.

She doesn’t answer, too absorbed in the giant bowl of ground pork and chives.

***

This is what cooking in our house looked like before The Woks of Life. A little of this, a little of that. Yes, there’s the imprecision that results when a recipe has never been written down but also the skill of cooking by feel, learned from hours of watching, tasting, and yes, smelling to see if there was enough salt to react with the raw pork in the dumpling filling to bring out (what I only now know is) a familiar savory aroma.

Having grown up with such priorities as watching the latest Disney Channel Original movie on Saturday nights and getting my mom to buy me frozen fettuccine alfredo from the grocery store(1)it was easy to ignore the master class happening just 20 feet from the television.

Don’t get me wrong. I did have a passion for food and cooking…just not Chinese cooking. It was the golden age of 1990s food television! I was constantly looking outside of our own home for inspiration.

I paid rapt attention to Ina Garten as she demonstrated how to throw the perfect dinner party for a succession of stylish, well-to-do friends. Kaitlin and I watched Iron Chef reruns to see just how many tiny dishes one could craft out of a load of spiny lobsters shrouded in the fog of dry ice, and pored through recipes in classic American cookbooks, discovering unknown terms like “quick bread” and “crudités.”

You should know—for my entire life, I’ve been a stickler for accuracy, control, organization, and efficiency.

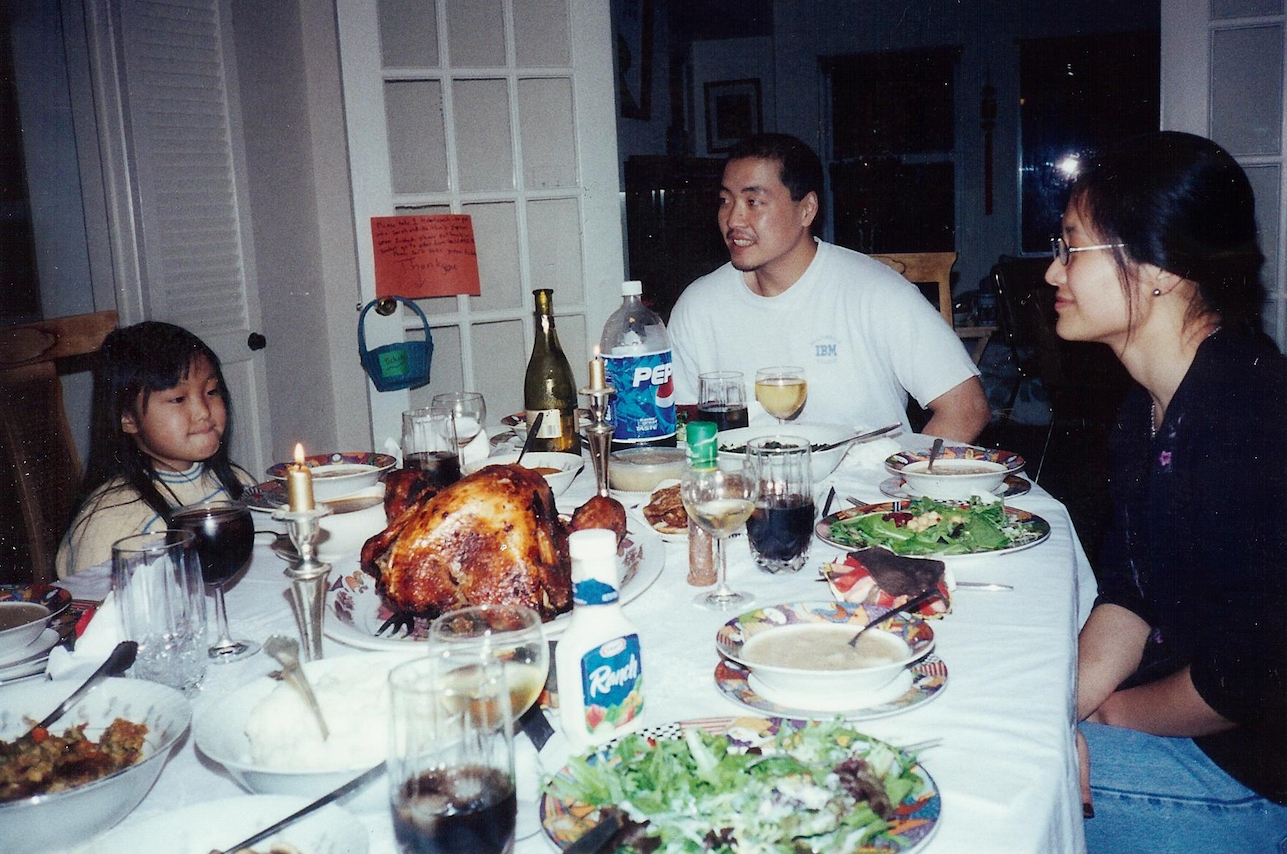

When I was little, Thanksgiving dinners were my chance to demand that everyone not simply say what they were thankful for, but provide their submissions at least an hour in advance of dinnertime, drop them into a small wicker basket, take their seats once the turkey hit the table, and then go around the table while I tracked their responses—all in order from oldest to youngest of course.(2)

So it’s no surprise that I began my kitchen pursuits cherishing decidedly non-Chinese recipes and cookbooks, where everything was laid out and indexed in orderly fashion.

Even with Ina, for every cavalierly placed block of cheese and pile of warm marcona almonds, there was a precise measurement, down to the last ½ teaspoon of black pepper or tablespoon of good Dijon mustard.

It was only when I began to flirt with the idea of adulthood that I had a dreaded realization: not only had I not attempted to cook the Chinese food I’d eaten growing up, there was no obvious book or Food Network show that could teach me how.

Those lessons would have to come from a source closer to home: my parents. I had straight up squandered 18 years of potential learning—I knew how to eat Chinese food but not how to cook it!

And now I would have to turn to my parents—with their sprinkling and drizzling and tossing and eyeballing. Could they take the art of cooking from experience and habit, and force it into cups and tablespoons for their hapless daughters?

As it turned out, we all could.

My dad acquiesced as I lectured him on the differences between dry and wet measuring cups.

My mom accepted that if she wanted her daughters to truly learn our food ways and traditions (and to ensure that others could replicate our recipes too), she would be better served by not using a little plastic spoon with the handle snapped off to measure sugar.(3)

While Kaitlin was two years behind me, even she knew that it was time to sit up and pay attention. And The Woks of Life took off.

With humility—I was born to do this. My proclivity towards accuracy and efficiency has only become more intense as I’ve gotten older. I order my grocery lists with the layout of the store in mind—produce, then meat, then dry goods, then cleaning products, then dairy—so I can get in and out as fast as possible.

When I go on a road trip, I know which store I’m going to stop at for provisions 3 hours and 40 minutes into the drive.(4) I conduct research the way other people blink—compulsively and without realizing I’m doing it.

We started with our home-cooked go-to’s, eventually branching out and attempting dishes that were once solidly in the domain of eating out. We unlocked the secrets to the batter for salt and pepper pork chops and figured out how to make clear, translucent dumpling wrappers for dim sum. And to our surprise, we picked up readers and supporters along the way.

As the blog grew in popularity, we also started to receive a steady stream of reader requests for dishes that we’d never personally tried, or sometimes never even heard of:

“I used to eat this dish with beef, snow peas, and this spicy sauce at my favorite restaurant, which has long since closed. I don’t remember the name of the recipe, but…”

“When I lived in Guangxi, a common comfort food was something like ground pork with steamed eggs on top. I’m trying to recreate it, but if you’ve ever had it…”

“I’m looking for a recipe for the curried cuttlefish I used to order at dim sum, but the restaurant has stopped serving it…”

We realized that we weren’t just putting out recipes, we were chasing memories. And as we got bigger, we were no longer just rebuilding our own past, we were doing it for countless others.

It was a realization that came with even greater pressure for accuracy. But the task of staying true to a beloved recipe isn’t as clear-cut as my perfectionist brain would like it to be.

It begs the question, what is the “truest” version of that recipe? The four of us routinely argue about what constitutes “the right way” to cook something. Is “the right way” dictated by the handful of restaurants we’ve eaten at over the last 30 years? The spot in Beijing that we used to love going to? A technique that my grandpa taught my dad?

We come out guns blazing to get our points across to each other, desperate to persuade and cajole, or simply to force an idea through these thick skulls that seem to be hereditary.

One of our most often-used, most contentious (and extremely hyperbolic) phrases: “No one does that!”

We’ve all been guilty of saying it. We say it with the full knowledge that we haven’t stood in every kitchen or spoken with every chef who’s ever attempted a certain dish. The hubris behind the statement becomes even more stark when we stop and think about the fact that food has fewer boundaries and distinctions than one would think.

Throughlines aren’t straight, but curved, bent, and overlapping, as recipes zig-zag through nations, states, and family kitchens. Boundaries between spices and flavors are blurred, and kitchen habits and standards evolve with every generation.

My parents are Cantonese and Shanghainese, but can we definitively categorize the dishes that came out of our kitchen growing up as Cantonese or Shanghainese? Or are they mixes of both, with some Americana thrown in?(5)

Ironically, living in China is what began to take that pressure off. In the U.S., you might choose between Mexican, Chinese, Italian, or Thai for dinner. In China, it was more like, “do you want Mongolian roast lamb, Cantonese roast meats, Yunnan rice noodles, or Sichuan hot pot?

Restaurants were usually region-specific, but they weren’t necessarily trying to serve the “definitive” versions of any one dish, and some prided themselves on putting their own unique spin on old favorites.

In my mind, Chinese food was steeped in tradition—rooted firmly in the past. In reality, it was still evolving and changing, even in its place of origin.

Despite what I’ve led you to believe, we ultimately don’t end up with perfection in our cooking. There’s no be all, end all, as much as we’d like to think so.

We end up with an interpretation, informed by our own experience and biases. In a lot of ways, how we develop a recipe isn’t all that different from how my parents used to cook—with the recollection of a flavor, instincts honed from the last few kitchen experiments, and the desire to make something taste good, period.

It’s not so much about whether your grandmother put split mung beans in her zongzi or not, or whether your favorite restaurant put more dark soy sauce in their braised pork belly than my mom does.

As long as that first bite still conjures an image of your grandmother wrapping sticky rice into bamboo leaves, or a memory of trying something new at a restaurant, we’ve done our job.

(1) If you’ve scarfed down a box of microwaved Marie Callender’s fettuccine alfredo and licked it clean, we could be friends.

(2) These instructions were not always followed in spite of them being CLEARLY written on a colorful piece of construction paper and posted on the kitchen door. Ahem.

(3) It was that tiny spoon that comes in the Chinese brands of instant cup noodles. And to be clear…when we’re off the clock, we still use it.

(4) Well, 3 hours and 37 minutes, but who’s counting?

(5) My grandmother’s recipe for Ketchup Shrimp comes to mind.